This is an overview of my thoughts on the use of synthetic datasets in health research. The text is adapted from an unsuccessful scholarship application, which was adapted from an earlier unsuccessful scholarship application, which was adapted from a talk I gave at the inaugural meeting of the UK Open Research Working Group at Aston University.

Transparency and reproducibility are fundamental principles of scientific observation and discovery, ensuring that science is “show me”, not “trust me”. But as health researchers, we also have to consider other pesky principles like “informed consent” and “minimising harm” and “confidentiality”. It’s why we don’t remove organs from unwilling prisoners. It’s why we induce tumours in mice instead of humans. And it’s why we prevent unrestricted access to sensitive research data.

Not sharing data might sometimes be justified, but it creates problems.

It can prevent scrutiny of the difference between the research that was planned, conducted, and reported, leaving the evidence-base vulnerable to questionable research practices and conflicts of interest—anything from unconscious p-hacking to fraud. It can frustrate efforts to reuse data for original, independent analyses. Sometimes controlled access to patient-level data is possible, but the process is often slow, expensive, and onerous.

A partial solution to these problems is the use of synthetic datasets. A synthetic dataset mimics certain useful statistical properties of a real dataset but contains no information that could be used to re-identify individual patients, so the dataset can safely be shared.

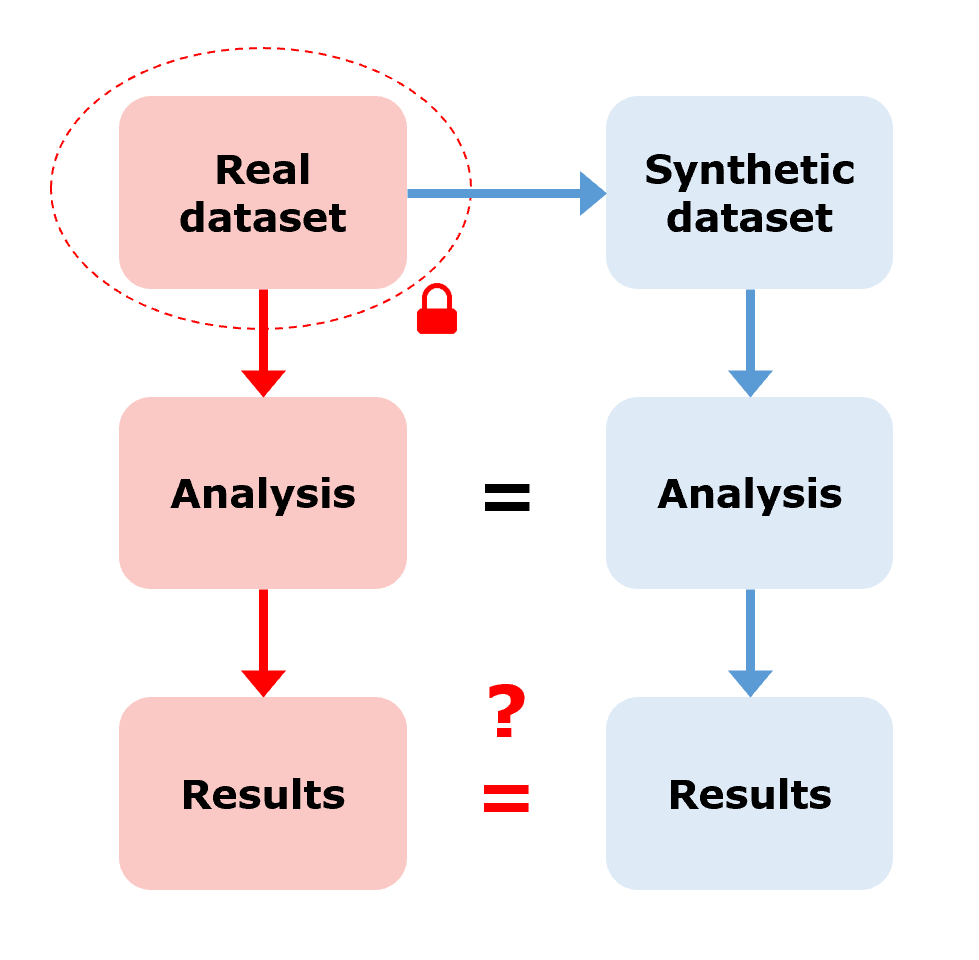

Synthetic datasets are perhaps most often thought of as supporting the use-case described in figure below: create a synthetic dataset from the real dataset, share it publicly, analyse the synthetic dataset as if it were the real dataset, and then, erm, hope that the analysis produces results that reliably replicate the results that would have been derived from real dataset.

In this use-case, we need high confidence that the synthetic results and the real results match, without actually being able to verify it. But I’m sceptical that, in all but the most simple or contrived scenarios, methods for generating synthetic datasets are good enough to guarantee this. We might have some theoretical guarantees on how closely the synthetic dataset mimics the statistical properties of the real dataset in certain types of data, but we don’t have any guarantees on how closely the synthetic results mimic the real results for any arbitrary research question or statistical model.

Without verifying the synthetic results against the real results should we trust them? Should we use them to inform treatment or policy decisions? I don’t think so but I would love to see examples where this has been done. Still, perhaps we should be prioritising improvements in responsible access to sensitive datasets rather than fobbing researchers off with datasets that we can’t guarantee will give reliable results.

There are, however, many other opportunities to use synthetic datasets in spite of—because of!—this unreliability. Let’s consider a few examples.

Ever tried to make progress on a project when you’ve been waiting months for access to the dataset? Synthetic datasets — Pow! Delays in data access or data collection is often the most disruptive bottleneck in a research project. Releasing freely-accessible synthetic versions of controlled datasets has the potential to stop infeasible studies early, reducing inefficiency, waste, and unnecessary re-identification risk. You can use synthetic datasets to write and test analysis scripts, resolve computational issues, design tables and figures… this list goes on. A script can be run immediately on the real dataset once access is granted, or else run by someone else who does have access. Sure, some changes may be necessary once the real dataset is available, but most major design hurdles will already have been jumped.

Ever felt guilty for tweaking your study design because the results weren’t what you wanted? Synthetic datasets — Bosh! Designs developed using synthetic datasets can be revised iteratively without concerns about data-dredging or post-hoc hypothesising since you know not to trust the results. This limits wriggle-room for you to bias your methods towards favourable results, consciously or unconsciously. Your study design should be agnostic to the results, after all. Synthetic datasets (or simulated datasets if data collection hasn’t happened yet and we need to generate data from scratch) can be used to pre-register studies in a manner much more precise than with vague allusions to “multiple imputation” or “non-parametric tests”, as the script will unambiguously encode the methodological design that converts the data into evidence.

Ever tried to adapt someone else’s code for your own use when you didn’t have access to the dataset it was intended for? Synthetic datasets — Kablamo! Even if you didn’t use synthetic dataset in the development of your study, if for whatever reason you can’t share your dataset, preparing a synthetic dataset afterwards facilitates the reusability of your analysis scripts. This helps other groups to repurpose or build on the study’s methods and increases the impact of your research.

Ever needed a big, messy ‘true-to-life’ dataset for teaching or training? Synthetic datasets — Doof! This doesn’t need much elaboration. Small or toy datasets are incredibly useful, but they have their limits. There’s only so much you can learn about complex datasets from iris and gapminder.

It’s bonkers that synthetic datasets are not used more often to increase research integrity and reduce research waste.

I’m looking at you, writers of the phrase “the dataset for this study contains confidential patient-level data and cannot be shared” without making any attempt whatsoever to mitigate the problems of research transparency and reusability that this raises.

I’m looking at you, PIs who obsess over being scooped, but aren’t concerned that your research isn’t reproducible.

I’m looking at you, custodians of every single birth cohort, disease or treatment registry, electronic health record, trial dataset, or administrative database on the planet who make researchers wait over a year for access to your data.

The point is, we can do so much more to improve research transparency and efficiency using synthetic datasets without worrying whether they can be trusted to reliably replace real datasets entirely. The methods and tools and tutorials are already here. Use them!